An excellent article by Joe Gardner on Charles Dickens and the authors fascination with death.

The timeless subject of mortality haunts the Victorian novel like the spectres abound in its cruder entries. Just as we as a culture are so enamoured with selfies and BuzzFeed sharing, so were our nineteenth-century ancestors indulging their idle inclinations by delving in death (Penny Dreadfuls in place of list-based click articles); reading about it, writing about it, painting it and most definitely playing audience to it whenever and wherever possible.

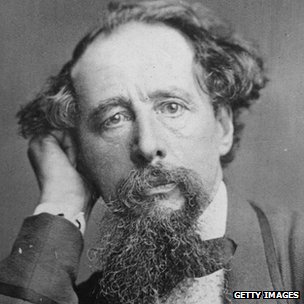

Author Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870) was a living legend in his day; an outright literary celebrity whose deserved influence on popular culture boasted no precedent – as such an ambassador for Victorian culture and, by extension, the peculiar, morbid fascinations it was notorious for. The self-proclaimed ‘Inimitable Boz’ was, far from being a stranger to the more macabre corners of his society’s contemporary interests, an active enthusiast of such grisly pastimes.

The topic of death was of as much interest to him as the societal injustices he strove to alert his wealth of readers to through his novels. And indeed, the impact of the latter would likely have been impugned without the lingering presence of the former. Would the plight of the poor have been as hard-hitting had socially-maligned characters such as Jo, Little Nell or even Fagin and Bill Sikes lived happily ever after?

Either way it can be argued that Dickens’ interest in the grim coda to Earthly existence may have been formed by his somewhat bleak beginnings – seeing his parents off to debtors’ prison in London as a boy new to the relentless city and swiftly sent against his wishes to work at a laborious blacking factory in Covent Garden (an ordeal which, though recounted in the proportionately-biographical novel David Copperfield, was kept strictly secret in the author’s lifetime, such was his overhanging shame of it). Dickens was denied a cosy childhood and so may have been psychologically nudged onto this darker path rather early on in life. The shame and degradation felt by the young prodigy may well have found clarity in his adult life via his notorious interest in death.

His lifelong proximity to mortality would forever shape his celebrated works. From the premature death of his wife’s sister Mary Hogarth burdening him with a sombre sense of the impending eventual, to his most famous festive misanthrope Ebenezer Scrooge being inspired by a (misread) name on an Edinburgh tombstone, the author and the passing of life are inextricably synonymous. In his earlier writings, Dickens developed a grim, gallows-humour method of dealing with the most upsetting of human trials which would remain and develop throughout his literary career. In Oliver Twist, the author has portly antagonist Mr. Bumble respond callously to the wasting away of an orphan boy in his own workhouse, flatly asking ‘Isn’t that boy no better?’ and swiftly following the enquiry with ‘He’s a ill-conditioned, vicious, bad-disposed parochial child that.’ Undoubtedly, through Bumble, Dickens is aping a sickly societal attitude of the day, though the dark humour underlying the sentiments is clearly that of a writer with an active interest in the macabre himself.

A perpetually active man, Dickens counted among his many hobbies frequent visits to cemeteries and, where possible, mortuaries. Of the former, Dickens counted the churchyard of St. Olave in Seething Lane, East London, ‘One of my best loved churchyards, I call the churchyard of St Ghastly Grim … This gate is ornamented with skulls and crossbones, larger than life, wrought in stone.’ He passed the place often during his beloved city walks and indeed the gateway to ‘St. Ghastly Grim’ is befitting Dickens’ pet name for the place, adorned to this day with sinister skulls which greet entrants to the sullen yard beyond. Cemeteries are abound in Dickens’ fiction, and are largely steeped in geographical precision. The shared burial site of Pip’s parents and still-born siblings in Great Expectations is based heavily off a real-life location in South West England, and the upsetting pauper’s graveyard described and illustrated in Bleak House is also informed by such sorry places found around the fringes of London in Dickens’ day. Furthermore, A Tale of Two Cities’ supporting player Jerry Cruncher holds a second, clandestine career as a ‘resurrection man’ (a grave-digger prone to selling body parts to doctors who had some difficulty acquiring them legally) in a sub-plot which is largely superfluous to the over-arching narrative of revolution and redemption but one which was clearly of such interest to Dickens that it couldn’t be sacrificed. Dickens frequented cemeteries; be it in life or on the page, he was always facing down a headstone with invested interest.

At the bemusement and, by and large, refusal of his friends John Forster and William Macready, the author would take excursions to witness recently deceased corpses first hand, and occasionally even observe the physical passing of terminal patients. A writer’s tool in research for his decidedly morbid subject matter perhaps, but one taken with such frequency and active interest that it is hard to believe Dickens found these events anything less than fascinating.

It is not to be said, however, that the author enjoyed death, or the abundance of it in poverty-stricken Europe. A public beheading witnessed during a holiday in Rome so disgusted him that he later wrote of it as an ‘Ugly, careless, sickening spectacle.’ Though it wasn’t so off-putting as to prevent the author later utilising the visual memory to staggering effect in the violent passages of historical revolutionary drama A Tale of Two Cities.

The fact that the poor were so belligerently neglected by the English government and aristocracy disgusted Dickens to the end of his life. He wrote in publications warning of an impending revolution akin to that of the French a century before, and, in one of his most celebrated prosaic sequences, imbued the death of Jo the street sweeping boy in Bleak House with authoritarian, savage indignation that serves as much as a moving death scene as it does a righteous essay on the societal indifference of Victorian England;

‘Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, Right Reverends and Wrong Reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with Heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us, every day.’

Tragically, and perhaps somewhat ironically, it is widely held that Dickens’ enthusiasm for the subject of death is what led to his own. Wishing to lace his beloved public readings with more dread and drama, Dickens took to performing a revised rendition of the death of Nancy from Oliver Twist. While audiences were captivated and startled by the grisly descriptions, nightly, energetic performances of such harrowing material may well have led to the author’s declining health, and his death from a cerebral haemorrhage aged just 58.