Today we celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, an event which I have studied closely in the past. Having already written a post on Wellington, the great hero of the battle, I thought I would focus here on another character- Major General Sir Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby. it’s a great story!

Ponsonby was the second son of the 3rd Earl of Bessborough and Lady Henrietta Spencer, daughter of the 1st Earl Spencer. During the Peninsular War he fought at Talavera, Badajoz, Salamanca, and was wounded at Burgos. He also fought at the Battle of Vitoria and The Battle of the Pyreenes. It was Frederick who gave the news to Wellington that Napoleon had been forced to abdicate.

During Waterloo Frederick took part in a ill-fated cavalry charge with the 12th Light Dragoons. They badly overstretched themselves and Frederick was very badly injured and left for dead on the battlefield. He was wounded in both arms, thrown to the ground by the stab of a sabre, and then pierced through the back. Over the hours that Frederick endured lying on the bloody battlefield, he met a Frenchman who promised to help him and gave him some brandy, was used as a shield from which another Frenchman shot at the British from, was trampled by oncoming Prussian cavalry, and plundered for his possessions; still he survived! At last he was spotted by a passing British foot soldier who stood guard over him until he could be taken to shelter. Miraculously he survived his many injuries, nursed back to health by his infamous sister- Lady Caroline Lamb.

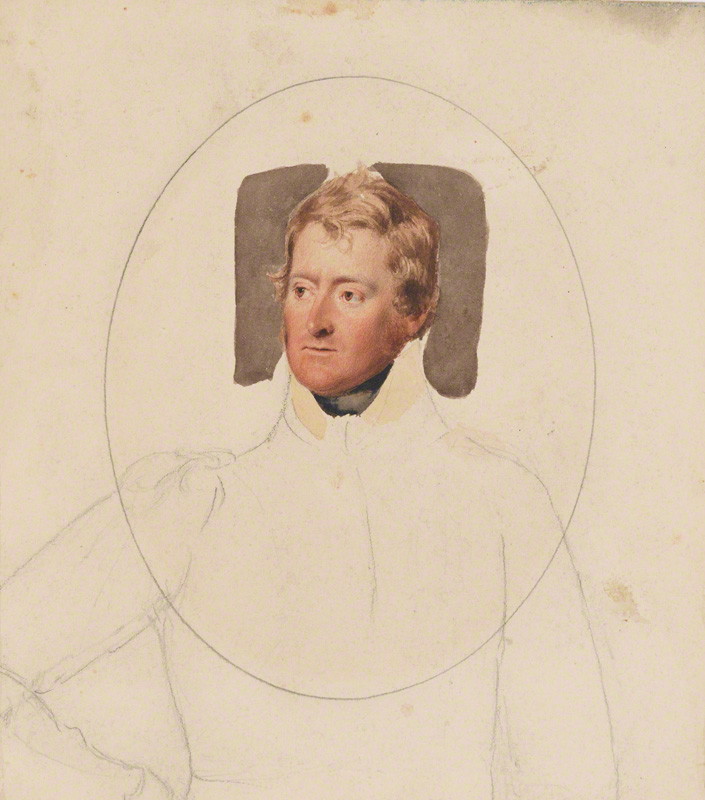

(c) English Heritage, The Wellington Collection, Apsley House; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation. On the left is Frederick and on the right Major-General Sir Colin Campebell

Frederick became quite famous for this adventure, although the exact details of it only came to light later. Frederick had wanted to keep the exact happenings of his traumatic experience away from his mother, who was bound to be shocked by them. Eventually though he was persuaded to tell his tale to Lady Shelley. Lady Shelley then wrote this long letter relaying the details to Lady Bessborough.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

It’s a very long account, so I have abridged some of it, but I promise it is worth a read! Over to Frederick…

‘In the melee I was disabled almost instantly in both my arms, and followed by a few of my men who were presently cut down—for no quarter was asked or given—I was carried on by my horse, till receiving a blow on my head from a sabre, I was thrown senseless on my face to the ground. Recovering, I raised myself a little to look round, being I believe at that time in a condition to get up and run away, when a Lancer, passing by, exclaimed : ” Tu n’es pas mort, coquin,” and struck his lance through my back.

My head dropped, the blood gushed into my mouth; a difficulty of breathing came on, and I thought all was over. Not long afterwards (it was then impossible to measure time, but I must have fallen in less than ten minutes after the charge) a tirailleur came up to plunder me, threatening to take away my life. I told him that he might search me, directing him to a small side pocket, in which he found three dollars, being all I had. He unloosed my stock, and tore open my waistcoat, then leaving me in a very uneasy posture. He was no sooner gone, than another came up for the same purpose, but assuring him I had been plundered already, he left me. When an officer, bringing on some troops (to which probably the tirailleurs belonged) and halting where I lay, stooped down and addressed me, saying he feared I was badly wounded, I replied that I was, and expressed a wish to be removed into the rear. He said it was against the orders to remove even their own men, but that if they gained the day, as they probably would, for he understood the Duke of Wellington was killed and that six battalions of the English army had surrendered, every attention in his power should be shown me. I complained of thirst, and he held his brandy bottle to my lips, directing one of his men to lay me down on my side, and placed a knapsack under my head. He then passed on into the action, and I shall never know to whose generosity I was indebted, as I conceive, for my life. Of what rank he was I cannot say; he wore a blue great-coat.

By-and-bye another tirailleur came, and knelt down and fired over me, loading and firing many times, and conversing with great gaiety all the while…Whilst the battle continued in that part, several of the wounded men and dead bodies near me were hit with the balls, which came very thick in that place. Towards evening, when the Prussians came up, the continued roar of cannon along their and the British line, growing louder and louder as they drew near, was the finest thing I ever heard. It was dusk when the two squadrons of Prussian cavalry, both of them two deep, passed over me in a full trot, lifting me from the ground, and tumbling me about cruelly—the clatter of their approach and the apprehensions it excited may be easily conceived. Had a gun come that way, it would have done for me.

The battle was then nearly over, or removed to a distance. The cries and groans of the wounded all around me became every instant more and more audible, succeeding to the shouts, imprecations, and cries of ” Vive l’Empereur,” the discharges of musketry and cannon, now and then intervals of perfect quiet which were worse than the noise. I thought the night would never end. Much about this time one of the Royals lay across my legs—he had probably crawled thither in his agony—his weight, convulsive motions, his noises, and the air issuing through a wound in his side, distressed me greatly—the latter circumstance most of all, as the case was my own.

It was not a dark night, and the Prussians were wandering about to plunder, and the scene in “Ferdinand Count Fathom” came into my mind, though no women, I believe, were there. Several Prussians came, looked at me, and passed on. At length one stopped to examine me. I told him as well as I could, for I could speak but little German, that I was a British officer, and had been plundered already. He did not desist, however, and pulled me about roughly before he left me. About an hour before midnight I saw a soldier in an English uniform coming towards me. He was, I suspect, on the same errand, but he came and looked in my face. I spoke instantly, telling him who I was, and assuring him of a reward if he would remain by me. He said that he belonged to the 40th Regiment, but that he had missed it. He released me from the dying man, and being unarmed, he took up a sword from the ground, and stood over me, pacing backwards and forwards.

At 8 o’clock in the morning some English were seen at a distance. He ran to them, and a messenger was sent off to Colonel Harvey. A cart came for me—I was placed on it, and carried to a farmhouse, about a mile and a half distant, and laid in the bed from which poor Gordon, as I understood afterwards, had been just carried out. The jolting of the carriage and the difficulty of breathing were very painful. I had received seven wounds; a surgeon slept in my room, and I was saved by continual bleeding—120 ounces in two days, besides a great loss of blood on the field.’

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

His injuries left him a hero, but partially disabled without the use of his left arm. In 1835 he married Lady Emily Bathurst, daughter of the 3rd Earl Bathurst, and went on to have six months. From 1826-35 he was Governor of Malta. it was during his time in Malta that Frederick the French soldier who had given him brandy on the field of Waterloo; which must have been a remarkable experience.