The Duke by Goya. Image: NGL

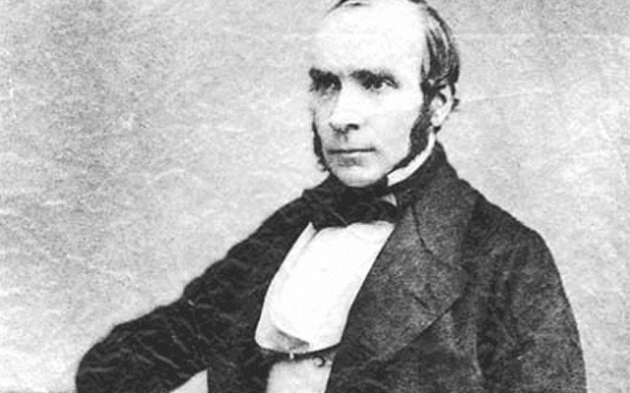

The Hon. Arthur Wesley was born the second son of an Irish peer in the County of Meath, Southern Ireland. As a child he did not impress either his peers or his parents, and the only great skill he showed was with a violin, which he played with exceptional skill. He studied for a short while at Eton, but it was at Angers in the military academy there that he found his calling. He returned to England in 1787 and immediately impressed everyone with his dramatic change of countenance and confidence. That year he was gazetted as an Ensign to the 73rd (Highland Regiment). By 1791 he was a Captain, but this was less to do with his military prowess and more to do with the buying of commissions; mostly with money lent to him by his older brother, Richard.

In the year 1793 Arthur turned his back on the artistic lifestyle in which his father (who was Professor of Music at Trinity College Dublin) and his mother had brought him up in. In order to show he was serious about his new career, he burnt his violin, and never played again. In the same year he was commissioned as a Major into the now famous 33rd Regiment of Foot. In September of the same year he became a Lieutenant-Colonel. Although it was with his regiment that he would win some of his most famous and glorious battles, he saw very little impressive action until 1796, when he set sail to India. In these years he represented the Constituency of Trim in Ireland, as many of his family had before him. Very few paintings of him exist before his victorious return from India, but a half-length by John Hoppner, still in the family collection, is perhaps the most precious record of what the young Arthur looked like. He is fresh-faced and confident, with the powdered hair that he would so soon cast off in the murderous heat of India.

Image: Government Art Collection

In India, Arthur acted as his elder brother’s unofficial adviser, Richard having been made Governor-General of India. In 1799 Arthur would make his name in the famous battle of Seringapatam, in which he defeated the Mysorean ruler Tipu Sultan, who had made the mistake of aligning himself with the French. After the battle, Arthur was made Governor of Seringapatam, and under his guidance helped restore the town to order again. He continued to secure the area, namely with the defeat of Dhoondiah in the following year. In 1803 he was promoted to Major-General, and the following exceptional battles took place in 1803: Assaye, Arguam and Gawilghur. In 1804 he was awarded the Order of the Bath, a great honour. The news took months to reach India, a record of it first being published in Madras in March 1805. When the medal finally reached Arthur in the hands of his friend Sir John Craddock, the hero was sound asleep, so Craddock pinned it to his chest; and let him sleep on. Although offered the command of the Bombay Army, Arthur was ready to come home. He believed ‘I have served as long in India as any man ought who can serve anywhere else’. Perhaps he knew that his skills as a leader could be put to better use on the European stage. He requested his return to England as a reward for having been awarded the Order of the Bath, and he arrived home on 10th September 1805.

On his return he (rather surprisingly) renewed his pursuit of Kitty Packenham, the pretty daughter of another minor Irish peer. Having had his suit turned down before his departure for India, on the account of his poor credit and what was still considered then to be poor career prospects, this time round he was warmly welcomed into the Packenham family. This was due of course to the fantastic sum of money he had made during his adventures in India, his fame in the English papers, and the fact that he was now a Colonel. Arthur and Kitty were married, despite the fact that neither had seen the other since before Arthur’s departure, and no correspondence had passed between the would-be lovers during their separation. Sadly, Kitty had lost the lustre of her English-rose beauty which had so attracted Arthur to her so many years before. Neither party was compatible, Kitty was a delicate, simple woman with simple needs. Wellington was neglectful, if not rather cruel to his new wife. They lived mostly separate lives during their long marriage, Kitty spending much of her time at Stratfield Saye, and Wellington in Apsley House. The marriage would never be considered a a success, although it did bear two sons. They would become the 2nd and 3rd Dukes of Wellington respectively.

In the wider political sphere, Napoleon’s had returned from Egypt and was turning his attention on the European stage. Arthur now had the chance to prove himself on a playing field nearer home. As the Peninsular War commenced in 1808, Arthur was made a Lieutenant-General and in July he sailed to Portugal to command some 10,000 men against the French. As a contemporary wrote around this time: ‘I was much struck by his countenance and his quick glancing eye, prominent nose and pressed lip, and saw, very distinctly marked, the steady presence of mind and imperturbable decision of character, so essential in a leader’ (Lieutenant Moyle Sherer).

Several famous battles followed, including the Battle of Rolica and Vimeiro, after which he was forced to return to England for a short time during the scandal caused by the signing of the Convention of Cintra. This gave the surrendering French rights beyond which the English people felt they deserved. After the death of Sir John Moore in 1809 Arthur returned to Portugal, where he forced the passage of the River Douro. He then crossed the border into France and beat the enemy at Talavera on the 27-28th June. For this success he was risen to the peerage and took the title of Baron Douro of Wellesley. He was later made a Viscount, taking the name Wellington, a name chosen for him by his brother William. Wellington liked the name immensely.

After French reinforcements arrived, Wellington retreated back and took the brave measure of waiting for the enemy to advance on him. It appeared to all that he was trapped, and that he was making a grave error. Wellington, however, had great confidence. He created the defense system known as the Lines of Torres Vedras. His plan worked, and Wellington was able to force back the French troops, led by Massena, all the way back to Salamanca. At the siege of Badajoz he was not successful, losing thousands of men. However, he finally managed to capture the city fortress, with great cost of lives, on 6th April 1812. For this achievement, Wellington was made an Earl, and later Duke of Cuidad Rodrigo. After the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July Wellington marched into Madrid victorious. This took place on 12th August. In the same month he was elevated to a Marquess, the Marquess of Douro, and granted £100,000 from Parliament. He was also appointed Generalissimo of the Spanish Armies.

This short victory was tempered by the failure to capture Burgos, even after a months siege. Wellington fell back to the Portuguese frontier where all the allied forces gathered together. The year was now 1813, and Wellington’s name was famous all across Europe. All the hopes of the English peoples, who feared a French invasion, where lain on his shoulders. Advancing into Spain, Wellington fought at the Battle of Vittoria, in which the French lost around 5000 men, as well as most of their guns and stores. After the battle, the carriage of Joseph Bonaparte, who was attempting the flee the battle, was captured. Inside was discovered hundreds of priceless Old Master paintings. As a gift of thanks from the restored Spanish Monarch after the Peninsular War, Wellington was allowed to keep them, and they formed the basis of the collection at Apsley House (today part of English Heritage). After this successful battle Wellington was promoted to Field-Marshal, and was gifted an estate in Spain. After Wellington had successfully forced the French army back into the own country, it was announced that Napoleon had abdicated. Wellington had been victorious.

Watercolour, 1814. By Juan Bauzil. Very little is known about this artist. Image: NPG

Once peace was declared, Wellington became Ambassador in Paris, and enjoyed the hospitality of the city which was suddenly filled with people from all over Europe. Wellington entertained them all, in a lavish house (now the French Embassy), as the newly appointed 1st Duke of Wellington. He was bestowed with all the orders that Europe could fling at him, and many gifts made their way into his hands. However, peace was not to last and Wellington was called upon to once again show the military skill which had enabled him to manipulate the field of battle so expertly during the Peninsular War. Napoleon returned from his place of exile on the Isle of Elba, and the field of battle was chosen to be in Brussels, near a place no one had ever heard of, called Waterloo. The night before the battle a ball took place, through by the Duchess of Richmond. During the night news reached Wellington of Napoleon’s movements. Many of the officers present hurried away to join their regiments, others enjoyed a last hurrah with their companions, and ended up fighting in their evening clothes! Of course, many would never return.

This was surely to become the most famous battle in British History. Without Wellington’s victory, Napoleon’s troops could have successfully re-invaded Spain and Portugal, easily crossing the sea and invaded England too. The battle took place on 15th June, 1815. But it was not a sure victory, in fact Wellington was sure that it was the closest rung thing of his life. At first it seemed that Napoleon and his French guns would succeed, but they failed to overcome the British on their first attempt, and were forced back. Fierce battles took place all day, and it seemed that either side could win if they held out for the other to collapse. Luckily for Wellington General Blucher and the Prussian Army arrived at the ninth hour, and was able to provide the backup needed to crush the French armies and achieve a victory for Wellington and the allied forces.

Achilles statue in Hyde Park. Depicting the victorious Wellington. Made out of melted down French cannons.

Napoleon abdicated on 22nd June 1815. Wellington returned victorious. His achievements had secured peace after Napoleon’s long and tyrannical rule across the plains of Europe. His position became almost idolatrous, but he himself never forgot the colossal human cost which had to paid in order to maintain peace. Viewing the fields of dead, he hoped a battle of this nature would never need to be fought again. Returning to England, Wellington was showered with honours from all of the European nations, of which he was naturally very proud. Gifted money from Parliament, he bought the estate of Stratfield Saye in Hampshire. The next year he would buy the grand Apsley House off his brother Richard, for much more than it was worth, in a vain attempt to help Richard out of his monumental debt. Not until 1818 would the Allied Forces finally be disbanded and Wellington would leave behind his military career forever, and embark on a new one in the political cattle market of Westminster.

Fulfilling various and numerous public offices, holding the reins of many institutions and organisations, as well as running his estates and entertaining his countless friends and admirers; Wellington seemed unstoppable. He certainly worked harder, slept less and wrote more than many of most of his contemporaries put together. In 1827 he was appointed Commander-in-Chief but resigned the position in 1828 when he became Prime Minister. The memorable achievement of his two years in office is of course the Catholic Emancipation Bill, but the cost of this Bill would split his party in two. Wellington was forced to resign. A year later, Kitty, his wife, died. Reunited at the last, hers had not been a happy or productive life.

Conservative in life as he was in politics, Wellington staunchly opposed the Great Reform Act of 1832. The people were rioting, causing trouble in the streets, and iron bars had to be fixed to the windows at Apsley House. Two years later, in 1834, Wellington was asked again to become Prime Minister, which he did from November to December; whilst Peel was travelling back from Italy. In 1834 he became Chancellor of the University of Oxford, a position he thoroughly enjoyed. Regaled wherever he went as a national hero and treasure, crowds would cheer him and follow him in his carriage. Artists clamoured more than ever to have a sitting with him, usually he would relent, with much grumbling; and often he sat to three at once!

by Alfred, Count D’Orsay, oil on canvas, 1845, Image: NPG

In 1846, after living more than half a century in the public gaze, Wellington removed himself from public life, and endeavoured to live a slower-paced life. Occasionally he achieved this, relaxing in his favourite spot, Walmer Castle; which was his to use as Lord Warden of the Clinque Ports. Keeping up his terrific number of correspondents until the day he died on 14th September 1852, he was mourned by the nation as the loss of greatest hero England had ever seen. Hundreds of thousands thronged the streets to watch his funeral procession, ending at his final resting place, Westminster Abbey.

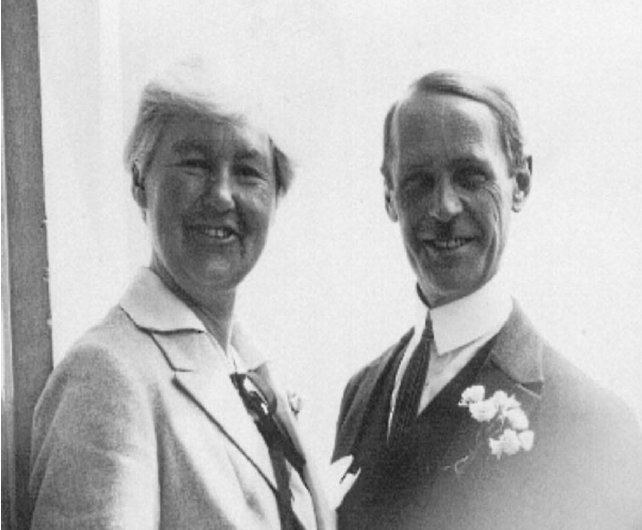

Flora was born into a hardworking middle class family from Yorkshire. Eschewing the normal forms of amusement for little girls, Flora adored horse-riding and shooting. She spent hours out of doors, running wild through the woods and fields around her home. Flora wished she had been born a boy so she could become a soldier, but this of course was absolutely impossible at the time. As she grew older, her sense of adventure and desperation to see more of the world could not be abated. As soon as she turned eighteen, Flora used her secretarial skills to travel to Cairo, across British Colombia and the United States. On her return she became of the first women in Britain to obtain a driving license and bought a French racing car. She joined the shooting club and trained with the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry.

Flora was born into a hardworking middle class family from Yorkshire. Eschewing the normal forms of amusement for little girls, Flora adored horse-riding and shooting. She spent hours out of doors, running wild through the woods and fields around her home. Flora wished she had been born a boy so she could become a soldier, but this of course was absolutely impossible at the time. As she grew older, her sense of adventure and desperation to see more of the world could not be abated. As soon as she turned eighteen, Flora used her secretarial skills to travel to Cairo, across British Colombia and the United States. On her return she became of the first women in Britain to obtain a driving license and bought a French racing car. She joined the shooting club and trained with the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry. Women were actually allowed to join the Serbian Army, something that would never had been allowed back in Britain. Flora jumped at the first opportunity to join as a private in the infantry. No British woman had ever done so before, so it really was an extraordinary thing to decide to do, in the midst of a war. The Serbs in turn greatly appreciated Flora’s commitment and many skills. She was the utmost professional, game for everything, but also had a humour and humility that endeared her to soldiers from all ranks. For the Serbs she personified Britain’s commitment to help them in their hour of need. Flora was also fantastically brave. She was twice mentioned in Dispatches, and was awarded the Serbian equivalent the Victoria Cross for her bravery during a particularly vicious attack. This attack left her seriously wounded from twenty-eight individual shrapnel injuries down one side. By this time she had been promoted to the rank of Sargeant- Major, and on sick leave in England, raised as much money as possible for her beloved Serbian troops. She returned to the front line in May 1917.

Women were actually allowed to join the Serbian Army, something that would never had been allowed back in Britain. Flora jumped at the first opportunity to join as a private in the infantry. No British woman had ever done so before, so it really was an extraordinary thing to decide to do, in the midst of a war. The Serbs in turn greatly appreciated Flora’s commitment and many skills. She was the utmost professional, game for everything, but also had a humour and humility that endeared her to soldiers from all ranks. For the Serbs she personified Britain’s commitment to help them in their hour of need. Flora was also fantastically brave. She was twice mentioned in Dispatches, and was awarded the Serbian equivalent the Victoria Cross for her bravery during a particularly vicious attack. This attack left her seriously wounded from twenty-eight individual shrapnel injuries down one side. By this time she had been promoted to the rank of Sargeant- Major, and on sick leave in England, raised as much money as possible for her beloved Serbian troops. She returned to the front line in May 1917. Flora was forced to endure three and a half years of solitude in Belgrade, cut off from friends and family. When the war ended Flora was free to return to England, but without her beloved husband, it was a difficult decision. However her sense of adventure had not diminished, and so Flora decided to go and live with her nephew in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). She loved living there but was forced to leave after only a few months as the locals were appalled to find her smoking and drinking with the African locals, in a fashion that was deemed totally unacceptable! Flora reluctantly returned to England, where she lived out her remaining years dreaming of more adventures. She even renewed her passport in the months before her death in 1956, in the hope that she might get to explore more of the world.

Flora was forced to endure three and a half years of solitude in Belgrade, cut off from friends and family. When the war ended Flora was free to return to England, but without her beloved husband, it was a difficult decision. However her sense of adventure had not diminished, and so Flora decided to go and live with her nephew in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). She loved living there but was forced to leave after only a few months as the locals were appalled to find her smoking and drinking with the African locals, in a fashion that was deemed totally unacceptable! Flora reluctantly returned to England, where she lived out her remaining years dreaming of more adventures. She even renewed her passport in the months before her death in 1956, in the hope that she might get to explore more of the world.